From dystopian landscapes to sensory connections – meet the innovators challenging the boundaries of creative expression. At the intersection of art, technology, and social commentary, four graduates from the University of the Arts London (UAL) are pushing the limits of what contemporary art can achieve. Hailing from Camberwell, Chelsea, and Wimbledon Colleges of Arts, each artist explores diverse yet deeply resonant themes – from Lingyue Hu’s dystopian landscapes critiquing humanity’s environmental destruction to Alicia del Pino Dolz’s sensory-driven projects that question human compatibility through technology. Nick Willis reimagines alternate realities in set design, while Rose Christie-Miller finds raw human emotion in the most unexpected spaces, like Berlin’s underground club culture. In this collective interview, these graduates share how their time at UAL has shaped their work and how they aim to impact the future of art and design.

BA (Hons) Fine Art: Computational Arts, Camberwell College of Arts, Class of 2024

hube: Your project appears to explore the aesthetics of dystopia and wasted landscapes, focusing on the tragic consequences of human interaction. What inspired you to get deeper into these themes, and how do you hope to provoke thought or conversation through your work?

Lingyue Hu: My exploration of dystopian themes and decaying landscapes arises from a profound sense of grief over the irreversible damage humanity continues to inflict on both the environment and society, particularly in this age of rapid technological advancement.

From an ecological standpoint, events like nuclear waste spills and the depletion of water resources are stark reminders of the escalating environmental crisis. On a societal level, unchecked industrialisation and the rise of hyper-intelligent technologies have worsened global conflicts, leading to atrocities on an unprecedented scale. The dominance of social Darwinism and reverse selection, which prioritise survival at the cost of ethical considerations, is becoming disturbingly prevalent.

Much like the unsettling visions seen in dystopian literature, the fragmentation of information in our society erodes critical thinking, disassembling coherent narratives. Through my work, I use visual language to forecast the dire consequences of human interference, aiming to provoke awareness of the looming threats of environmental collapse and social destabilisation.

h: The concept of a ‘chaotic system’ seems central to your work. How do you translate complex theoretical ideas into visual forms, and what challenges do you face in making these concepts accessible and engaging for a broader audience?

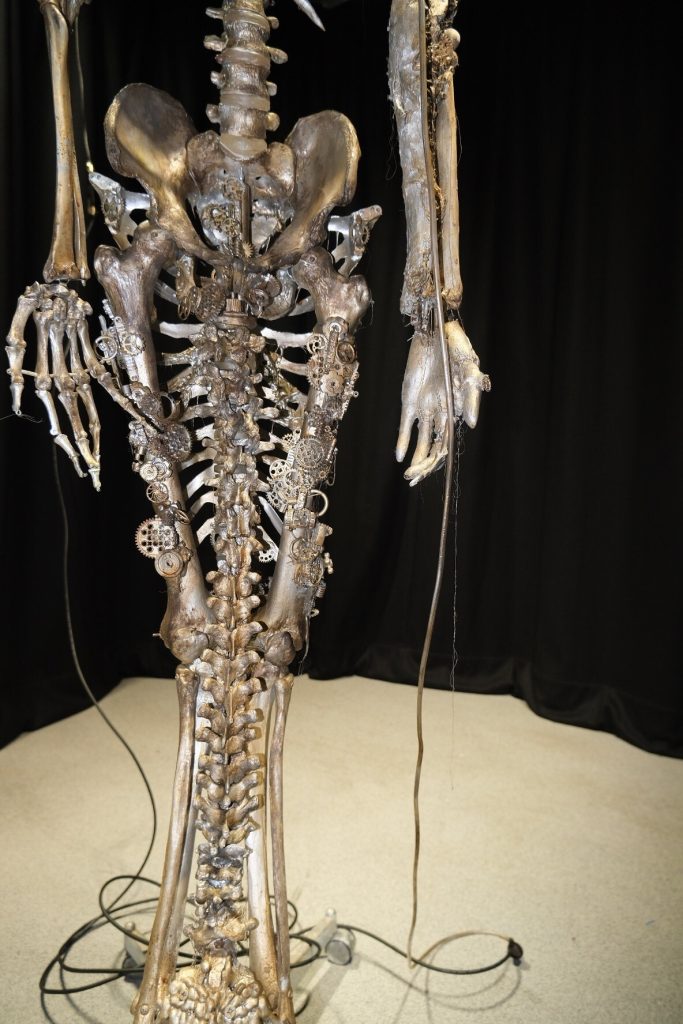

LH: I draw upon chaotic art styles, utilising predominantly visually metallic yet environmentally friendly, recyclable, and degradable materials to represent the paradox of disorder caused by human intervention.

In my work, I explore temporal chaos through the incorporation of steampunk mechanical elements and futuristic transparent materials. These choices make the piece appear weathered by war, embodying a sense of time that feels disoriented. The blurred timeline invites the viewer to question whether the destruction is from the past, present, or future.

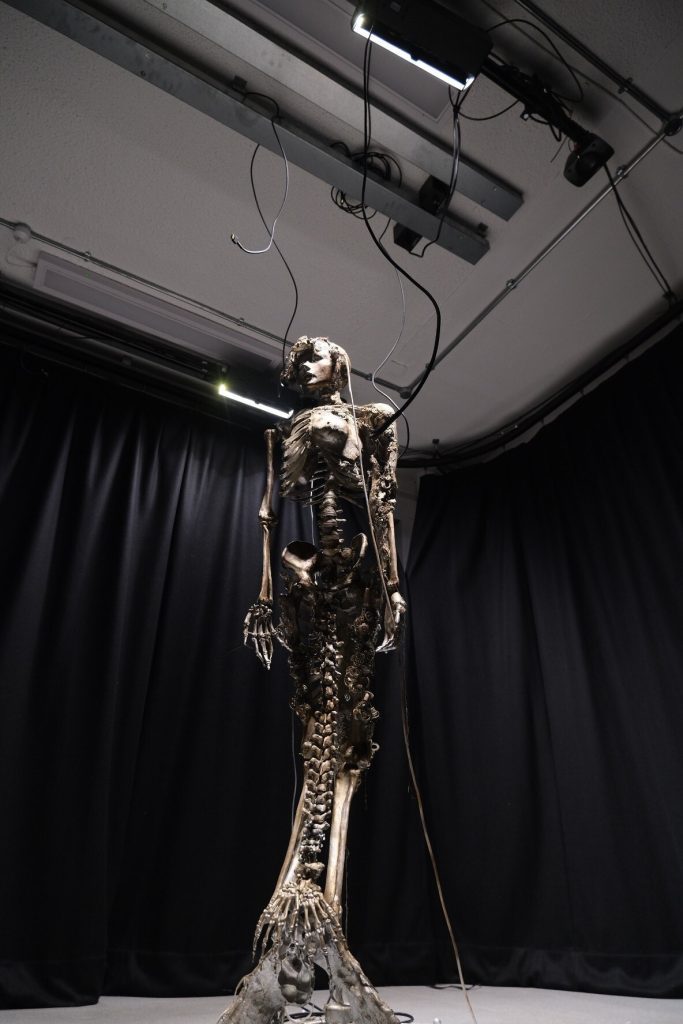

Through wasteland aesthetics shaped into marine life forms, I investigate spatial chaos, where human interference disrupts the natural order. By breaking the self-similarity of nature and merging oceanic forms with lands, I ask whether this signifies the collapse of nature itself.

The burn marks and rust in the sculpture symbolise the past, while the melting elements suggest both motion and stillness, encapsulating temporal chaos once again. This interplay raises the question: is the catastrophe frozen in yesterday, today, or an unknown future?

Finally, my work also reflects functional chaos. Burdened by utilitarian motives and complexity, it mirrors my turbulent existence. In this state, order and chaos coexist, embodying my restless and unsettled self.

h: Your work reflects a strong narrative around the doomsday aesthetic and the irreversible impact of human actions. How do you use visual elements to convey the urgency and gravity of these themes?

LH: My work aims to convey the urgency and gravity of humanity’s irreversible impact by using visual elements that mirror the chaotic disruption of natural processes. The fragmented body of the mermaid, for example, represents how biological self-organisation, viewed through the lens of chaos theory, has been shattered by external human interventions. These uncontrollable forms serve as a critique of recent incidents like nuclear waste leaks, which have disturbed the natural self-regulating processes of marine ecosystems.

In chaos theory, Belousov observed that a chemical mixture could oscillate between murkiness and clarity without external interference, suggesting a reversible, self-sustaining system. In contrast, my artwork draws attention to how human actions – such as the misuse and depletion of water resources – have interrupted these natural cycles, leaving behind barren wastelands where life once thrived. By visually portraying this degradation, I aim to evoke a sense of urgency around the consequences of these disruptions. posterity

h: Considering the dystopian and tragic themes in your project, what do you hope viewers will take away from your work? Do you see it as a form of cautionary tale, or is there an element of hope or redemption?

LH: The sense I aim to leave with viewers is doubt. I want them to question their role in environmental degradation and how it may shape the future. My work oscillates between tragedy and hope, and I leave it to the audience to decide its meaning.

I also critique how technology shapes our behaviour and environment, drawing on ideas like technological feudalism and hegemonic infrastructures. Inspired by Yuk Hui’s critique of human-centric technology, I encourage viewers to rethink their relationship with nature and technology and consider whether we can break free from this destructive cycle.

h: How has your education at UAL helped you in translating complex theoretical ideas into visual forms? Are there specific aspects of the curriculum that you found particularly beneficial?

LH: My time in the BA (Hons) Fine Art: Computational Arts course at Camberwell College of Arts has been instrumental in helping me translate complex theoretical ideas into visual forms. As I delved deeper into things like comprehensive analyses, research, and cultural contextualisation aspects, I found that they added layers of meaning to my artwork, allowing me to articulate my ideas more fully and thoughtfully.

The curriculum’s emphasis on realising ideas, analysing work with intersectional awareness, and maintaining ethical practices has been particularly beneficial. My first art project, which was based on physics theories, marked a turning point for me. After presenting it to my tutor, Alex Veness, I found myself over-explaining and apologising for my language skills and emotional expressions. He reassured me, saying, ‘You don’t need to over-interpret yourself for others, nor do you need to apologise frequently. I hope you can always maintain this poetic, mysterious, and turbulent state’. His encouragement helped me embrace my unique artistic voice and approach, which has been crucial in translating complex concepts into visual forms.

h: How do you perceive the role of modern education at UAL in addressing the global issues that your work touches upon, such as environmental degradation and dystopia?

LH: At Camberwell College of Arts, the interdisciplinary approach has empowered me to address global issues like environmental degradation and dystopia through my art. The curriculum encourages critical thinking and combining theory with practice, allowing me to explore the intersection of creative expression and societal concerns. For example, my mermaid sculpture critiques human impact on oceans, using eco-friendly materials, and stands as a reflection of how UAL fosters awareness and engagement with real-world issues through art.