Internationally recognized for his distinctive curatorial vision, Larry Ossei-Mensah has organized exhibitions and public programs across major cultural hubs worldwide. His tenure as Susanne Feld Hilberry Senior Curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, as well as Curator-at-Large at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, resulted in such projects including Parallels and Peripheries, Let Freedom Ring. Beyond his institutional roles, he has organized such shows like The Poetics of Dimensions at Art Basel Miami Beach (with ARTNOIR & UBS) and an expanded version at the ICA San Francisco—exhibitions that navigate identity, diaspora, and social transformation with clarity and intent.

In 2013, he co-founded ARTNOIR, a collective dedicated to amplifying the voices of artists of color and expanding representation within the fine arts. During the 2019 Venice Biennale, the Ghanaian-American Ossei-Mensah contributed an essay highlighting the work of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye for the first-ever Ghana Pavilion. In 2023, he co-curated the 7th Athens Biennale with OMSK Social Club and further advanced global discourse on contemporary art.

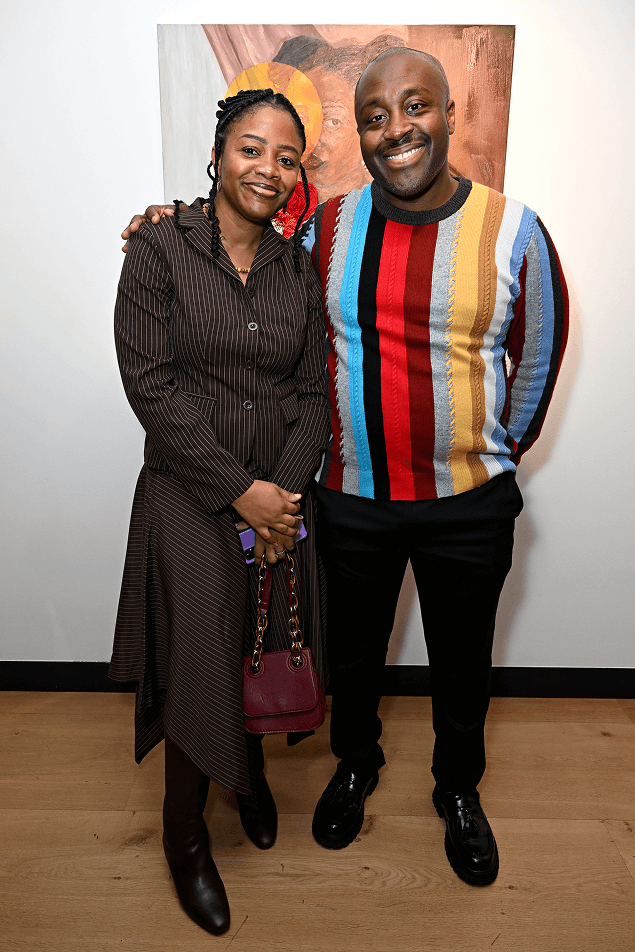

Most recently, following his role as a judge for the Paul Smith’s Foundation x Winsor & Newton International Art Prize, Ossei-Mensah has taken on the mentorship of Cecelia Lamptey Botchway—the Prize’s New York winner and a Ghanaian mixed-media artist whose tactile works explore womanhood, community, and material memory through textiles. Across his exhibitions and writing, he remains a powerful advocate for equity, imagination, and access within the art world—helping to ensure that the next generation enters a field ready to sustain and elevate their voices.

hube: What initially compelled you to take on a mentorship role, and what have you discovered about yourself through teaching and guiding others? Can you recall someone who once played that role for you—a figure who shaped your own trajectory?

Larry Ossei-Mensah: I was recommended by Ekow Eshun, a great friend and colleague who previously participated. He shared the value, and it encouraged me to look into it. As a curator, much of what I’ve learnt has come from doing and experiencing IRL. I’ve also benefited from mentorship in my own career. In 2016, participated in the ICI Curatorial Intensive in New Orleans, and that was a game-changer for me—next year will mark a decade.

It’s been a constellation of individuals who’ve supported me throughout this journey—pushing me when I need that push but also being the sounding board when I needed that, through this constellation of individuals—not just one person—who’ve been supportive in the practice but a pleathra of folks such as: Thelma Golden, Franklin Sermons, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Klaus, Deborah Willis, Mickalene Thomas, Klaus Biesenbach, and Derrick Adams.

I feel blessed to have people show up exactly when they’re needed. I’ve been lucky to be part of a network of mentors, peers, and friends I can speak with, learn from, and reach out to whenever necessary. It’s something important in personal growth—not just in the art world but in life. I understand the value of mentorship and an opportunity like this for an emerging artist or an artist in general, because we often have the misconception that mentorship is only between older and younger artists. I don’t think that’s necessarily accurate.

It’s more of an exchange of ideas and helping an individual understand and expand their lens of possibility. You have your own personal experiences—you’re thinking through how to manifest them through your work as an artist, curator, or writer. Sometimes life brings individuals into your world who may say, ‘That’s great, but have you thought about this?’

We get absorbed in our day-to-day—in our bodies, minds, and spirits—so it’s powerful to meet someone who recognizes your potential, who sees possibilities you haven’t yet imagined, or sees them clearly and simply offers tools or insight to adjust your approach.

h: What stood out to you about Cecilia Lamptey Botchway’s practice that made her a compelling choice for the Paul Smith’s Foundation & Winsor & Newton International Art Prize?

LOM: She was someone I have been watching because she’s of Ghanaian descent, and I try to watch all the artists in the ecosystem. Moreover, my review process was a practical and intuitive choice, and then it’s a curatorial one. Her training in textiles, as part of the skills that encompass her practice, made her a compelling choice.

Thinking about an artist who has an understanding of textiles, fabric, and material—she’s been able to move in and out of it—making textile-driven works but also paintings that incorporate mixed media. I liked this oscillation, which gestures towards fluidity. This work, particularly the one on view, is profoundly personal. It’s a self-portrait. She just became a mother; she’s trying to re-examine her role in this world as a mother, woman, artist, and creative.

If you look at the painting, it’s almost like sunlight over the eye, which could also be a magnifying glass—this moment of reflection, both for the viewer and for her as an artist. I’ve always been drawn to work that incorporates mixed media, and she’s been able to do that seamlessly, in an interesting way.

A prize like this can be an incredible catalyst for an artist’s practice. Even being at the opening last week, it was great to see all the artists in dialogue and exchange—you have artists from Shanghai and Antwerp. I hope that this becomes a group that stays in contact and continues to dialogue beyond this project.

Resiliance, 2026