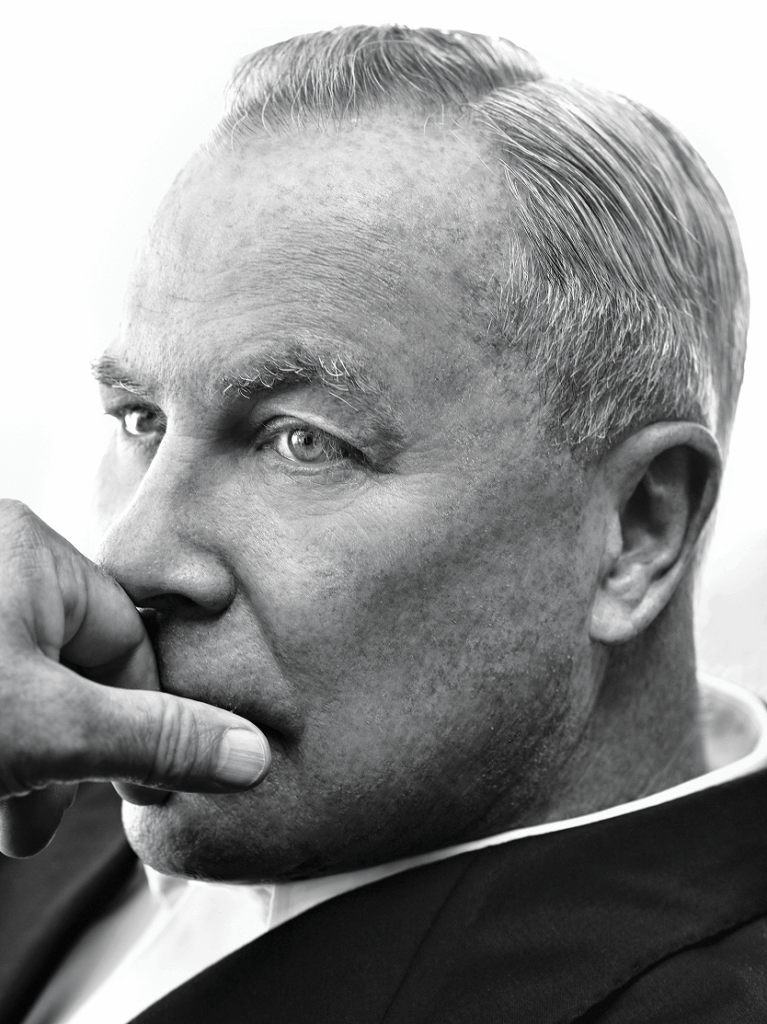

This interview was conducted shortly before Robert Wilson passed away. We are profoundly grateful to have spoken with the master of light, space, and sound about the arc of his life and the spirit of his work—a conversation that illuminates, in its own way, the breadth of his visionary nature.

“Perhaps it is our dreams that carry the hope we need to keep moving forward,” Robert Wilson told us. Over his 83 years, he certainly had many. In a recent tribute to the late director, Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan said that, like Lewis Carroll’s White Queen, Wilson often dreamed “six impossible things before breakfast.” Oneiric or otherwise, his imagination has redefined the language of the stage—bending narrative, space, time, and form in avant-garde works whose impact the world is only just beginning to understand. His collaborators were visionaries, too. William S. Burroughs, Lou Reed, and Marina Abramović; Philip Glass, Willem Dafoe, and Mikhail Baryshnikov. A creative cohort whose kaleidoscopic brilliance can be also found at The Watermill Center—the arts laboratory in upstate New York that Wilson founded in 1992.

In an open letter to André Breton, Louis Aragon—one of the founding Surrealists—described Wilson’s work as “what we, from whom Surrealism was born, dreamed would come after us and go beyond us.” That vision endures. “All of my work is a time-space construction,” Wilson said. “It is where I start and where I end.”

hube: Art has a complex relationship with reality and illusion, truth and fiction. While these distinctions often feel unnecessary when we talk about art, if we accept them for a moment, is creativity for you an escape from reality or a search for it?

Robert Wilson: I think that art is truth, and indeed very mucha part of reality. At the same time, it can betotally artificial. In my work, I often say to anactor on stage, “I don’t believe you”—evenwhen I am directing something in Chinese,Japanese, Hungarian, or another language Ido not understand. Truth is easily understood. The body does not lie. Just look at the body: it tells you everything.

I am just now in my hotel room. In fact, I have spent most of my life in hotel rooms. There is a TV, which I keep on—but I very rarely turn the sound on. That way, I am able to see more; I see different things than I would if the image was accompanied by sound. I am able to see a kind of truth: the body does not lie. And I think that is true, no matter what you do. In the performing arts, for example, if you are singing, I do not even need to hear your voice, I can just look at the body and know when it is wrong, when it is not true. Truth is something deep inside. It is a language that anyone can understand, wherever they may be from.

h: If creativity is a kind of dialogue, does that dialogue end with the performance? Or does it continue to live and evolve over time—for both the audience and the artist?

RW: The dialogue with the audience is why we make theatre. Maybe we make it for ourselves first; great actors are those who perform for themselves first. But still, they always keep in mind that it is also for the public, and learn how to have a dialogue with the public. That dialogue must remain open. For that reason, my work is not interpretive. As a director, as a designer, as an actor, my responsibility is to ask questions, and not to say or interpret what something is.

When I was 12 years old, I learned Hamlet, or part of it: How all occasions do inform against me,

And spur my dull revenge! What is a man If his chief good and market of his time

Be but to sleep and feed? a beast, no more.

I can say it every day. I am 83. I started saying it when I was 12. And every day, I can think about it differently. There is no single way to think about Hamlet, that’s why it is a masterpiece. Each time we say it, we reflect on it in a new way. I might read it one night in one way, and the next night completely differently. This work is about asking questions: “What am I doing? What am I saying?” And if we already know exactly what it is that we are doing, then there’s no reason to do it. The reason to work is to ask “What is it?”—not what something is. Keep it open!

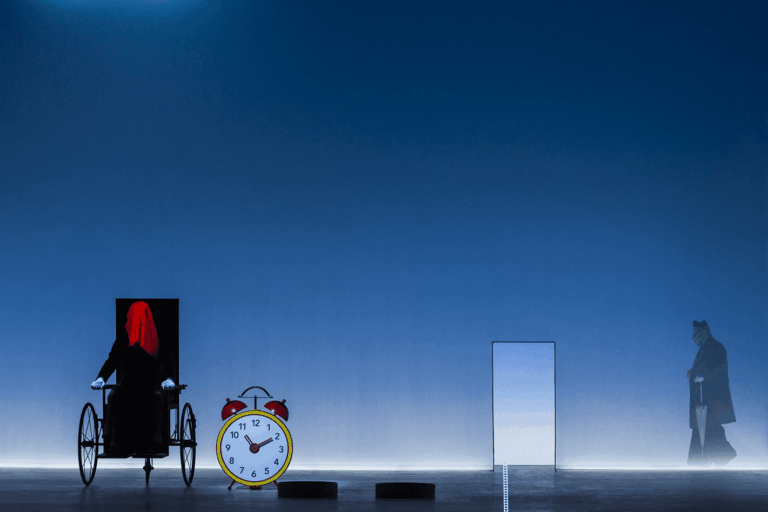

Photography by YIORGOS KAPLANIDIS

Performed at Teatro della Pergola, Florence, 2024

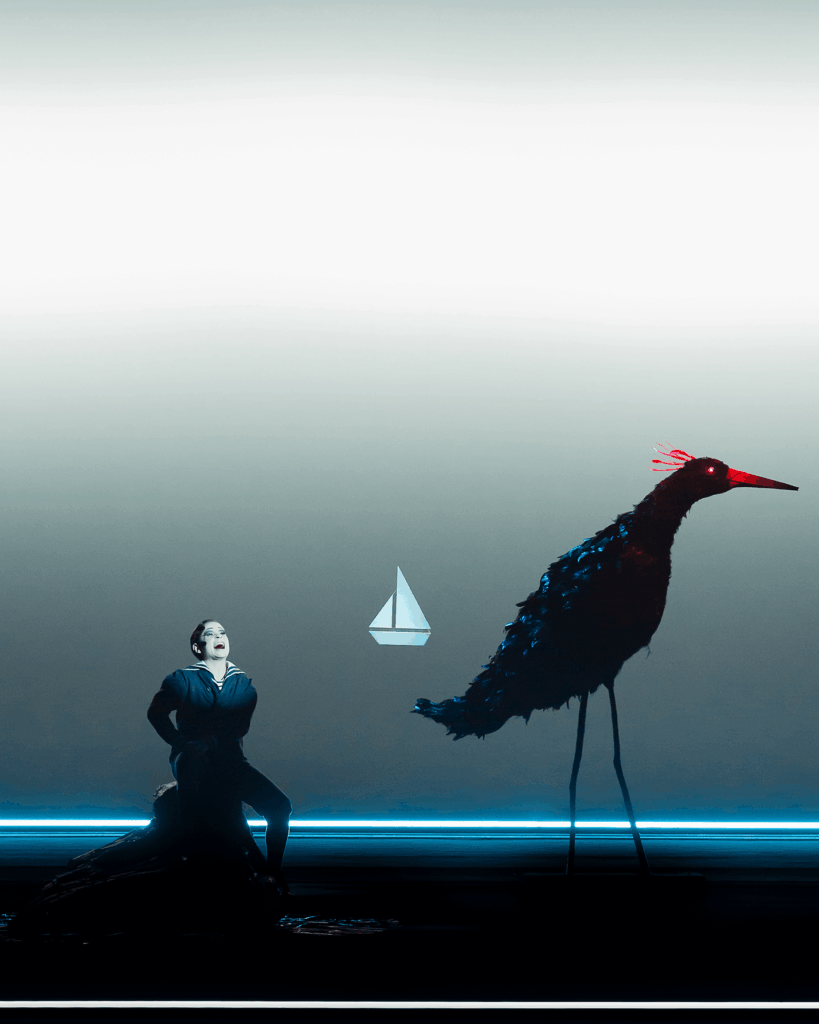

Photography by FILIPPO MANZINI

Performed at the National Theatre of Greece, Athens, 2012

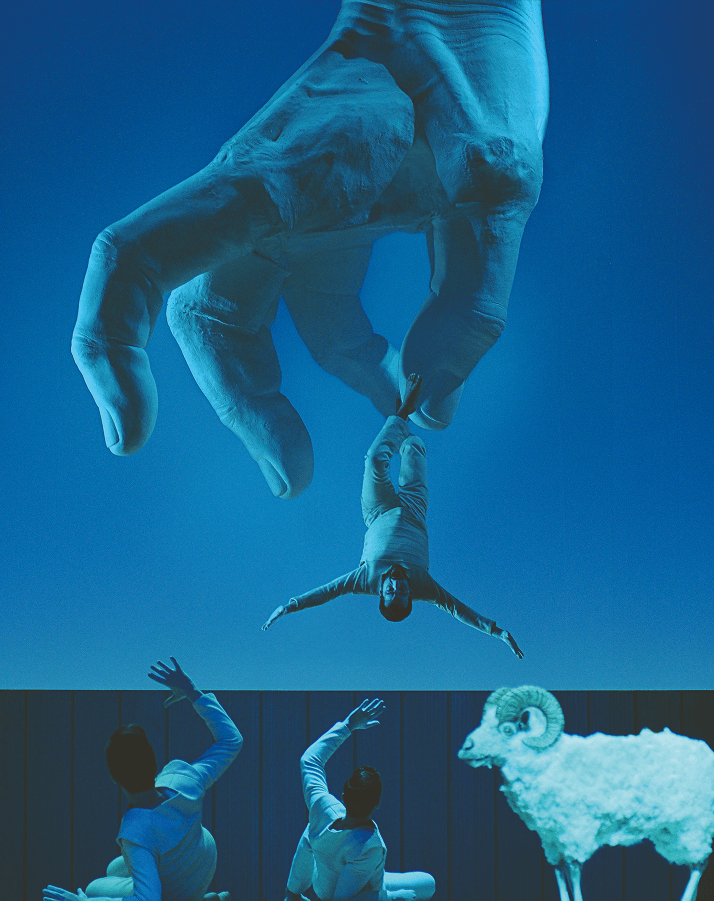

Photography by EVI FYLAKTOU