Join us for an in-depth interview with Walter Van Beirendonck, where he opens up about the legacy of the Antwerp Six, the role of fashion in activism, and his continuous exploration of diverse expressions of masculinity.

hube: Let’s go back to the very start and the story of the Antwerp Six, which is truly legendary. How did the Antwerp Six happen?

Walter Van Beirendonck: That is a long story. But what is important to understand is that it all happened very spontaneously. We never planned to be the Antwerp Six. At first, we were just a group as friends, and we were all hard-working and ambitious. At school, we worked a lot together, we travelled together, we became fascinated by a lot of things together, and went to parties and concerts together. And then, as we started to work in fashion—on our own collections or for other commercial projects—we felt like we had to get out of Belgium. In Belgium, we felt a bit stuck. We were getting a lot of press coverage, but from the Belgian media, and we had never had the opportunity to be seen internationally. It was very frustrating. So, partly out of frustration, partly out of ambition, we decided to get out of Belgium and go somewhere where the fashion press can discover us. We decided to head to London, because at the time London was a very dynamic place. You had people like BodyMap working there. Our friend Geert Bruloot, who later opened his shop in Antwerp, was going to London for a fair. And he had an idea that we should come along and bring our collections to present them there as a group. So, we rented a tiny 4m2 van, put all of our collections in there and drove to London. And that’s how we started to present our work as a group and that was the beginning of the Six.

h: This was in the 1980s, which was a turbulent decade, both politically and for design. Did you feel like the time called for change?

WVB: Again, I have to say that much of what we did was completely accidental. We didn’t feel that we had to do anything. We just wanted to become known internationally at the time when very few people from the fashion department had international success. The school was unknown and Antwerp was not a famous fashion city. We were just trying to get out. But we were extremely inspired and motivated by what was happening in fashion around that time. While still at school, we were aware of what designers like Mugler, Montana, Gaultier were doing. Around the same time, Rei Kawakubo, Yohji Yamamoto started coming to Paris. And in Italy, Armani and Versace were having a moment. These were all very individual, very distinct, very strong voices in fashion. It felt like an explosion of creativity. It was very motivating for us to see that you could make an individual statement and create something new, something that had never existed before. It shifted from Pret-a-Porter to this brilliant designer boom. It was very stimulating to see that happen, and we were enjoying it a lot—we went to fashion shows and hustled for invitations. We were such dedicated fashion victims!

h: But going back to this aspect of politics which, to me, is quite interesting and which, I feel, is very present in your work. In the 1990s, during the terrifying AIDS pandemic, your collections remained defiantly sexy and unapologetically queer. Specifically, I am referring to the collections Paradise Pleasure and Astral Travel. And I was wondering, if you could talk a bit about that time and about those collections?

WVB: Absolutely, political statements are, and have always been very important to me. I think when you have a platform as an artist, an actor, or a singer, you can change things for the better. More than that, I think you have to do that—when you have that platform, it is your responsibility to use it for good. I realised early on that fashion was an excellent communication tool, and how you could communicate efficiently with fashion. When I was a teenager, David Bowie was the artist, from whom I learnt how you could use your image, your clothes, your makeup to make statements. That’s how I discovered the power of fashion. In the ’90s, the effects of the AIDS epidemic were overwhelming, they were shattering. I still remember the first images of AIDS patients and how the media called AIDS a sickness of homosexuals. It was a horrible time. Around me, a lot of people were getting sick, people were dying. I felt it was important to speak up. And I turned to the medium I knew, and I used my storytelling to raise awareness about AIDS and the necessity to use condoms. My mascot, Puk-Puk, which I created around that time, was wearing a condom, and we did small features with Puk-Puk putting on his condom for the sake of a safe future. The Paradise Pleasure collection, a rubber collection, was about safe sex, and fetish, and the top models, who were famous at the time, had their faces covered. But at the same time, it told the story about the beauty of this world, and we were showing projections of nature during the show.

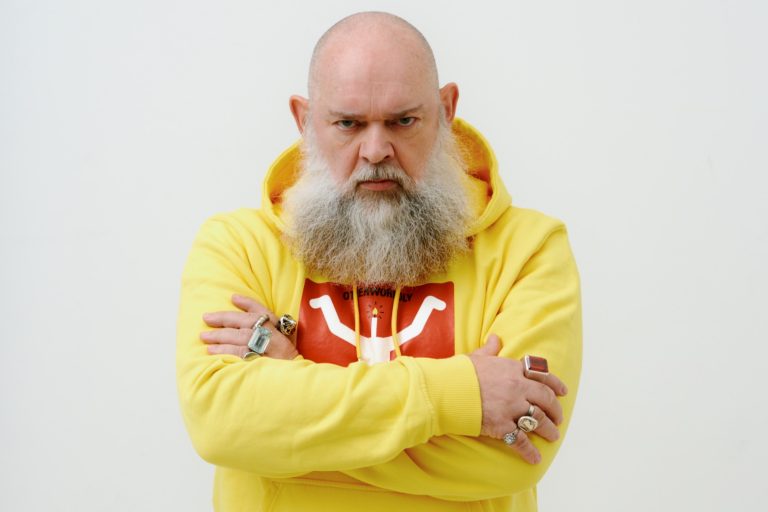

h: You’ve mentioned David Bowie was a huge inspiration. Bowie is famous for his androgynous image and, similarly, you’re often called a pioneer of the ‘new masculinity’. What do you think about this designation and who is the man that you show in your collections and design for?

WVB: The most important thing for me about the men that I show is diversity. That’s what I have been focusing on since the beginning of my career. From the start, I have worked with completely different types of models. In my early Baby Boy collection, I worked with big guys who were not typical models. I’ve been using street casting, and I’ve been casting very different-looking models. So, for me, there’s no perfect masculinity. I don’t have a set idea for a certain kind of man, or a certain kind of masculinity, but I am flexible in the way I think about men and humans. Over the years, I’ve been interested in gender fluidity, too. In the ’90s, I experimented with hairdos on boys, but for me, it was more of a fashion statement than a comment on gender.