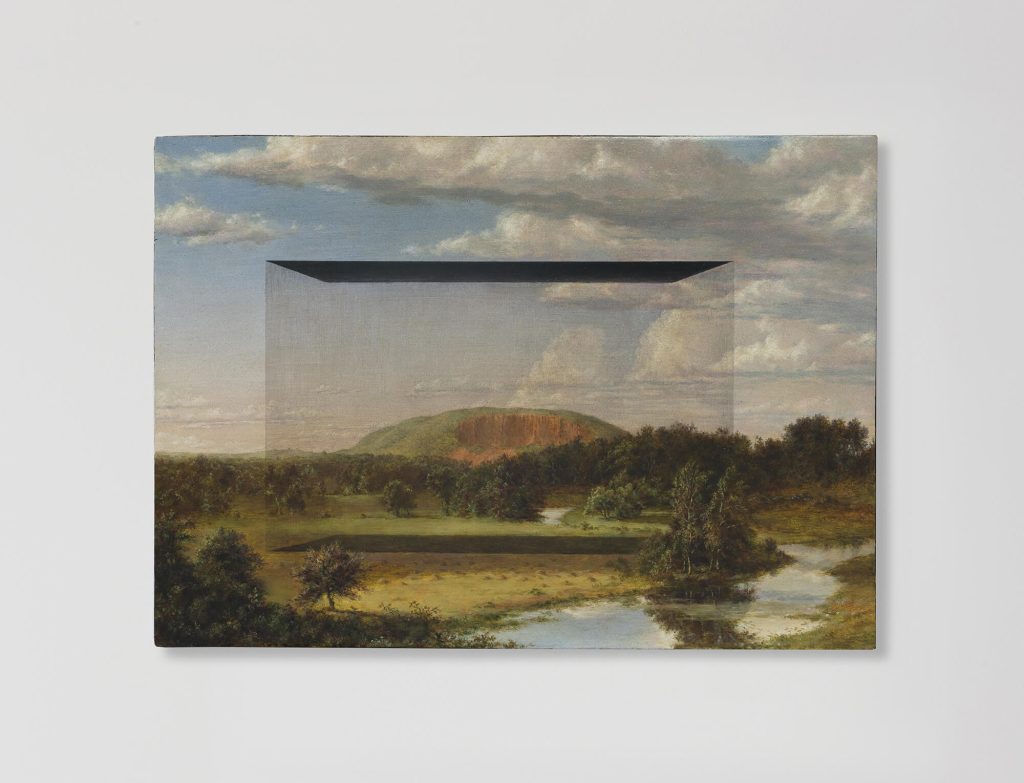

Studies into the Past

oil on wood, painting: 27 1/2 x 39 1/3 x 1 9/10 inches

Courtesy of LAURENT GRASSO and SEAN KELLY, New York/Los Angeles

Studies into the Past

oil on wood, painting: 13 3/4 x 19 11/16 x 1 3/4 inches

Courtesy of LAURENT GRASSO and SEAN KELLY, New York/Los Angeles

Laurent Grasso’s Artificialis, which premiered at the Musée d’Orsay, takes viewers on a cinematic journey through a world where the boundaries between the artificial and the natural dissolve. Blurring the lines between reality and virtuality, the work challenges our perception of the environment, evoking the spectral territories of the post-Anthropocene era. Through this monumental installation, Grasso explores the shifting notion of exploration and captures a moment in time when our reference points have completely unravelled.

hube: Your exhibition Artificialis explores the intersection of nature and technology. How did the use of LIDAR scanners and hyperspectral cameras shape the narrative of Artificialis?

Laurent Grasso: Most of my projects deal with the idea of invisibility. I focus on realities that are real but obscure or difficult to perceive. When working on a project, I think of film and sound not only as vehicles for information but also as signals – visual, colour, sound, frequencies. These are elements I try to incorporate into my practice.

To extend this exploration of the invisible, I’ve always used different technologies, often new ones. They engage our brains in ways that we’re not used to. For example, I’ve been filming with drones for over 30 years. At the time, they offered a perspective that was not commonly available, a free, aerial view that felt connected to dreams or altered states of consciousness.

I’ve used photogrammetry, LiDAR scanners, and other cinema tools, but I also want to put the camera in non-human, autonomous machines, which are not controlled by humans but are more like free, independent entities. It’s not directly tied to artificial intelligence, but there is a similar element in the sense that I’m projecting a view that isn’t completely human, something more liberated.

The LiDAR scanners, for example, were originally used by scientists for archaeological research, helping to discover ancient Maya ruins. The technology allows us to see different materials, giving us a unique perspective on the world I used scans of Amazonian forests, as well as ice floes in the polar regions and many other places. This technology creates a new reality, a new kind of exploration, which fits perfectly with my concept of artificiality. Through the scanners, I add another layer to express this idea of discovering the invisible.

h: In Artificialis, you collaborated with musician Warren Ellis, who composed the soundtrack in real-time. How did this collaboration influence the atmosphere of the film?

LG: The collaboration with Warren was key. Artificialis was commissioned by the Musée d’Orsay as part of a show about the concept of nature. My contribution focused on exploring the future of nature, which was especially interesting considering the lockdown restrictions. For the first time, I couldn’t travel to shoot, so I organised a massive digital collage using stock footage, 3D scanning, and other technologies.

The lack of physical movement added an interesting layer to the project, fitting with its themes of virtuality and artificiality. We had to get creative with the editing process, which was intentionally mechanical and somewhat brutal. And sound was a huge part of this. Warren Ellis created a soundtrack that was hypnotic and fascinating, and it enhanced the atmosphere by complementing the collage of sequences and environments we created.